Kommersant Weekend

01.09.2023, 00:02

Russian Parisian Tatiana Antoshina (born in 1956) became a star of domestic feminist art in the 1990s, when there was neither a special fashion for it nor persecution of feminism. The issues of feminism and cosmism, the two main subjects of her creative work, are interpreted in various media, from ceramics and embroidery to video installations, but always with a sense of humor.

Text: Anna Tolstova

This text is part of the project “Finding a Place. 30 Years of Russian Art in Faces,” in which Anna Tolstova tells how artists of different generations worked with the new Russian reality and the Soviet past.

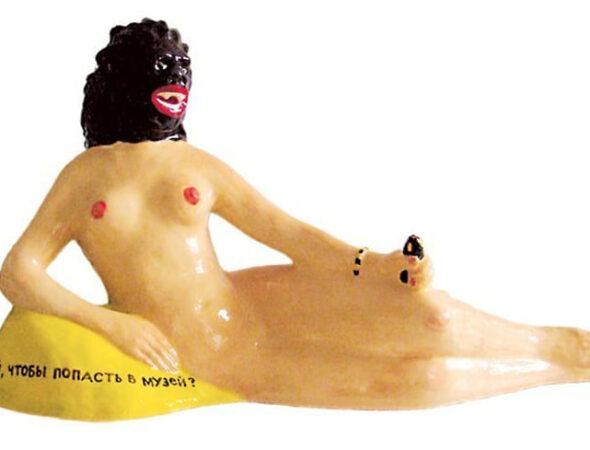

“Men are the fairer sex,” Tatiana Antoshina said mischievously in an interview with the “Kultura” TV channel in 2002, in connection with the exhibition “Art of the Female Gender” held at the Tretyakov Gallery. If feminism in Russia were not considered a dangerous thought crime but, on the contrary, had firmly established itself in the public consciousness, Antoshina could have rested on her laurels as the matriarch of domestic feminist art. However, the word “matriarch” does not quite fit the image of a charming fragile and eternally young woman who served as a model for Andrew Logan, was a mother, a candidate of art history. It was during her preparation for the candidate exams that she came across a question in the spirit of the Guerrilla Girls: why is almost all nude art in European art history of the female gender? And she set out to rewrite history in the photo series “Woman’s Museum” (1997), where, in live scenes based on masterpieces of the Renaissance, Baroque, Romanticism, and Modernism, played out by herself, her husband Alexey Tobashov, and other representatives of the Moscow art scene, men and women swapped places. In other words, the ladies bring David’s “Oath of the Horatii” (the scene shot in the underground vestibule of Belorusskaya-Koltsevaya is particularly colorful, with Tatiana Arzamasova from the group “AES+F”), and muscular “odalisques” cool off in Ingres’ “Turkish Bath.”

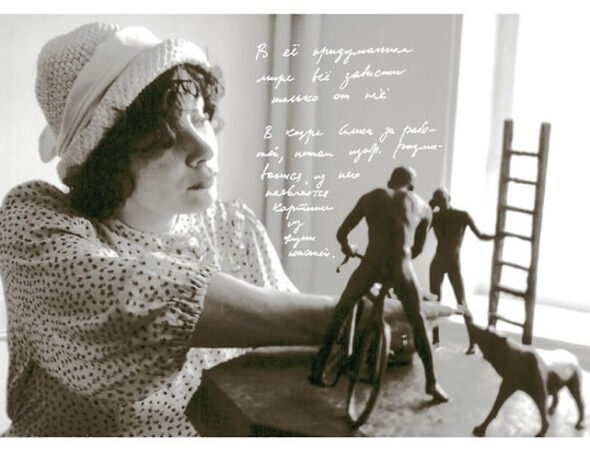

Antoshina came to Moscow to continue her education and study ceramics from a scientific perspective. Her parents worked at the Abakan Pedagogical Institute, where she spent her childhood. Her father was a well-known literary critic, and their home was often visited by Moscow guests, writers, and poets. Drawing and literature became a part of her life from an early age, and these interests manifested in her artistic works. Ceramics, which she engaged in, seemed unsuitable for lightness, improvisation, and humor, but Antoshina found a way to incorporate these elements into her works. She created projects that combined ceramics with other media, experimented with forms and materials. In her works, one can see the influence of literature and fairy tales, as well as an interest in gender issues and historical characters. Antoshina not only created her own works of art but also conducted research in the field of ceramics. Her scientific approach and knowledge of art history helped her create unique and original works. In her projects, Antoshina not only played with gender roles and historical characters but also used elements of humor and self-irony. Her works often evoke a smile and joy, and participants in her projects always display happy and cheerful faces. Thus, the ceramic artist Tatiana Antoshina brought a fresh perspective and humor to the world of art, combining traditional ceramics with modern ideas and themes. Her works are characterized by lightness and originality, and she continues to actively create and inspire others with her creativity. However, the brightest childhood memories were associated with another side of her father, a lover of skiing and fishing. Memories of the nature of Khakassia and Southern Siberia, seen through the eyes of a dreamy girl, filled Antoshina’s most magical and dreamlike works, such as the sculptural series “Asia, or the Dream Factory” (2002) and the installation “Cold Earth” (2014-2017), where the viewer is invited to mentally sit on a train and travel to the distant snowy land of the artist’s childhood. She studied painting at the Krasnoyarsk Art School, and sculpture and ceramics at the Krasnoyarsk Art Institute. As an excellent student, she was hired to teach at her alma mater, and her students received a medal at the VDNKh exhibition. However, she soon had to flee from Krasnoyarsk to Moscow. By not allowing her female ceramic students to be sent “to the potatoes” (a derogatory term for being expelled), she went against the party’s institute leadership. Her anti-Soviet behavior attracted the attention of the KGB, and pursuing a doctoral degree in art history at the Stroganov Academy became her salvation from further troubles.

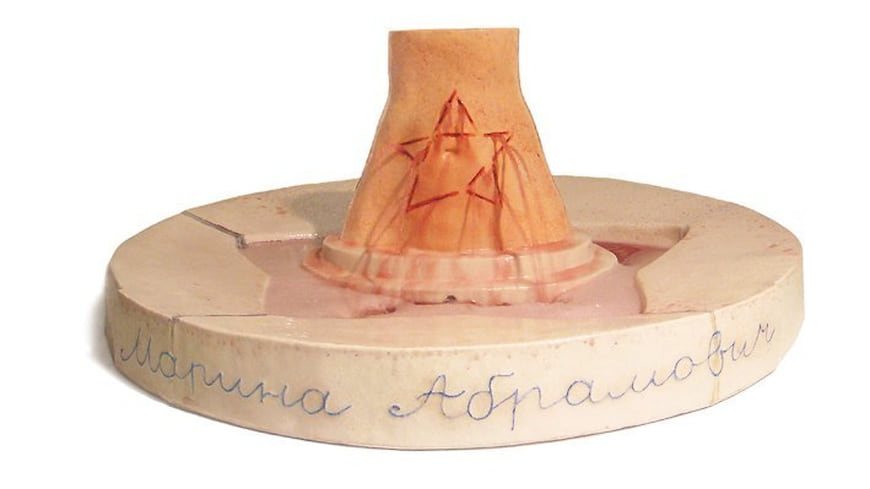

Tatiana Antoshina once said, “You open a book on the history of art, and all you see are naked men.”

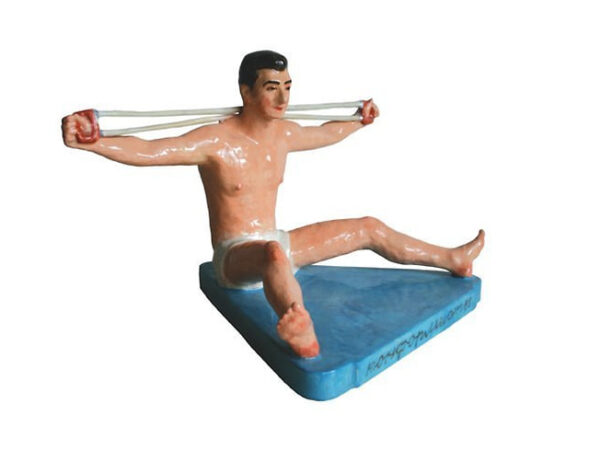

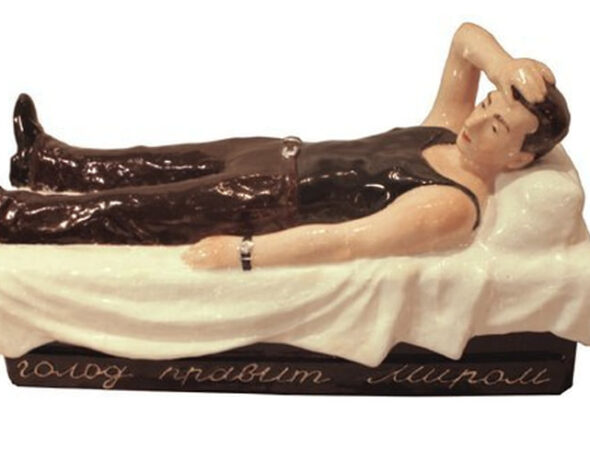

However, the topic of her dissertation, “Primitive Ceramics as an Artistic and Aesthetic Phenomenon,” was something she had been passionate about for a long time, both as an artist and from her interest in archaeological excavations in the Khakass-Minusinsk basin. This interest can be seen in her early works, which were stylized to resemble primitive pictographic vases and pots, housed in the Khakass National Local History Museum. While studying the works of Levy-Bruhl and Levi-Strauss in the Lenin Library, she maintained connections with the art community and soon became friends with leading figures of contemporary art in Moscow. She had some prior knowledge of Moscow’s art scene, as she subscribed to the avant-garde journal “Decorative Art of the USSR,” which was popular among practitioners during the pre- and post-restructuring years. In the mid-1990s, Antoshina began collaborating with Marat Gelman, one of the leading figures in Moscow’s art scene at the time. Her major exhibitions of the 1990s and early 2000s took place in his gallery. Working with Gelman allowed Antoshina to continue her experiments with ceramics and performance art. One of the exhibitions commissioned by Gelman was dedicated to Marat Gelman himself and was titled “Brenner” (1997). Antoshina created a series of miniature ceramic monuments, paying tribute to Gelman’s key actions and provocations. These figurines, stylized as agitational porcelain statuettes, became an original form of documentation and glorification of Moscow’s actionism. The idea of ceramic monuments to art and artists was further developed by Antoshina in the series “My Favorite Artists” (2007-2008). In this series, she depicted Masha Chuykova, Elena Kovylina, and other world-renowned artists alongside Marina Abramovic, Valie Export, Judy Chicago, Matthew Barney, Boris Mikhailov, Ai Weiwei, and the Guerrilla Girls. Later, she also created several sculptures dedicated to Pussy Riot. In the “Brenner” and “My Favorite Artists” series, Antoshina merged ceramics and performance art, creating unique and original works that documented and glorified the actionism and art of that time. “Performative” ceramics learned to engage with other media such as painting, graphics, video, textiles, becoming part of installations. Antoshina’s experience in interior design, which she pursued with her husband and sons in the mid-1990s when art did not bring any money, proved useful in her work with space. However, the installation “Quantum Leap” (2015), where all elements of a typical post-Soviet interior – a coffee table, armchair, patterned carpet, clock, dishes – slightly skewed and deformed, as if leaping into another dimension or energy level, indicates that design was not just a profession for the artist but a purely artistic endeavor. “Quantum Leap,” exhibited at the pavilion of Mauritius, became her first work for the Venice Biennale.

“Olimpus”, stage photo from series Museum of a Woman, 1997

“Cards players”, stage photo from series Museum of a Woman, 1997

“Are you jelousie?”, stage photo from series Museum of a Woman, 1997

“Conformist”, from series Brener, 30X40X25 cm., ceramics, 1997

“Hunger rules the world”, from series Brener, 22X42X18 cm., ceramics, 1997

“Good view”, stage photo from series Voyeurism of Alice Guy, 2002

“Sculpture I”, stage photo from series Voyeurism of Alice Guy, 2002

“To the Dock”, ceramics, glass, stainless steel, 1996

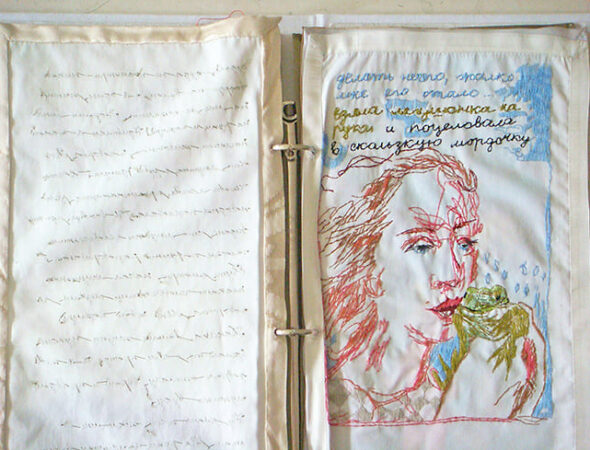

“Queen Frog”, embroidered book, 1999

“Under the Bed”, from series Asia, 2010

“Boy drinking Water”, from series Asia, 2010

“Guerrilla Girls”, from series My favourite Artists, 2008

“Vanessa Beecroft”, from series My favourite Artists, 2008

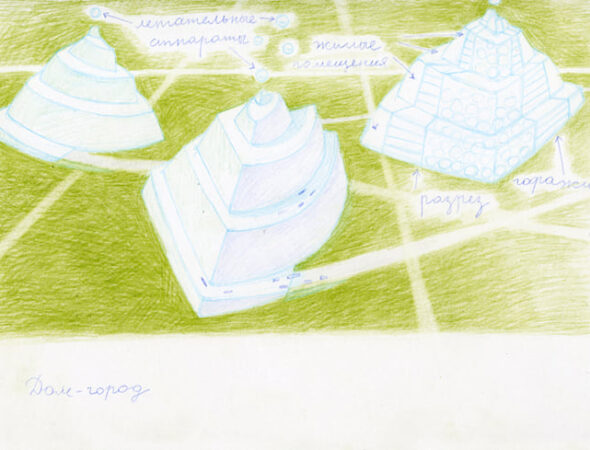

“Pyramid”, from series Visionary Drawings, 2009

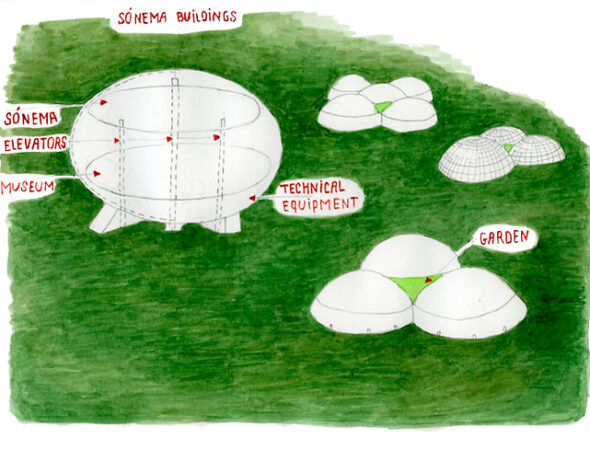

“Sonema”, from series Visionary Drawings, 2009

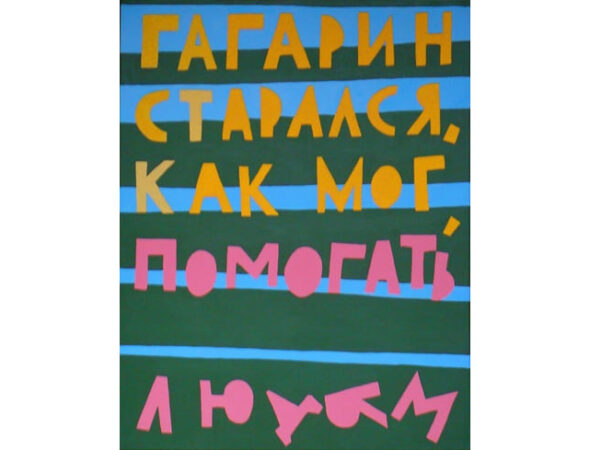

“Gagarin Tried”, from series Alice and Gagarin, acril/canvas, 90X70 cm., 2010

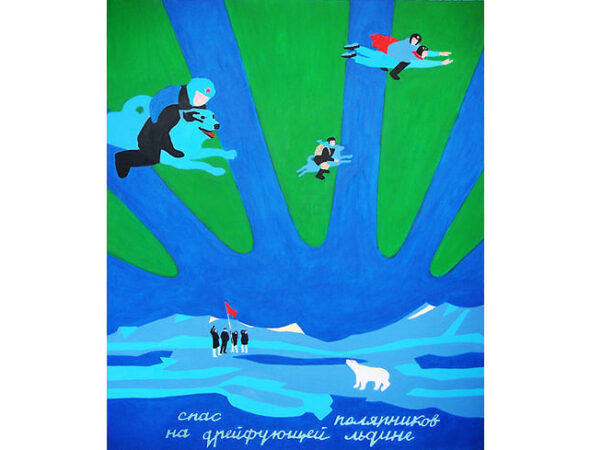

“Polar Explorers”, from series Alice and Gagarin, acril/canvas, 120X90 cm., 2010

“Alice you fly like a Girl”, from series Alice and Gagarin, acril/canvas, 90X120 cm., 2010

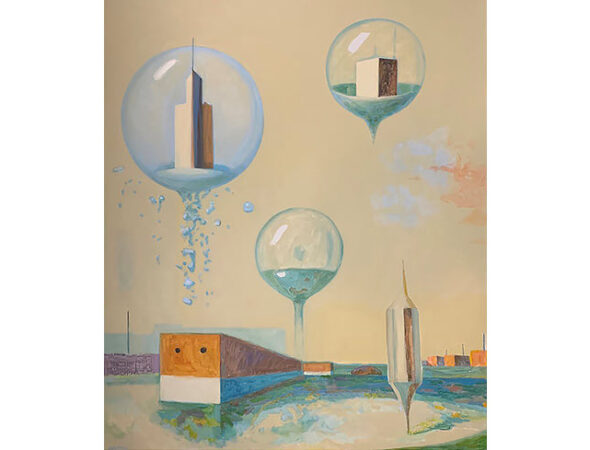

“Flooded Square”, from series Cold Land, installation, rubber/wood/steorin, 2014

“Quantum Leap” 56VB, installation, wood/fabric/ceramics/glass/plastic/brass, 2015

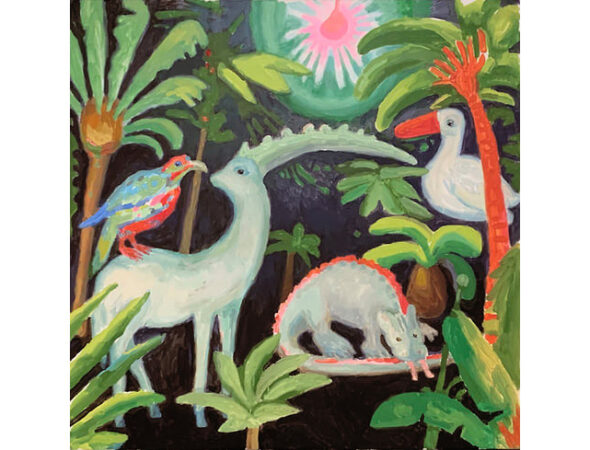

“Magic Forest, Planet EOS-1”, from series Space Ark, acril/canvas, 100 x 100 cm., 2023

“Escape”, from series Space Ark, acril/canvas, 200 x 170 cm., 2023

“Dragon”, from series Space Ark, chamotte/slip/glaze, 30 x 65 x 18 cm., 2018

“Heron”, from series Space Ark, chamotte/slip/glaze, 18 x 30 x 35 cm., 2018

Antoshina not only observed Moscow’s actionists but also Moscow’s conceptualists, becoming infected with the idea of personality from them. In the early 2000s, the figure of the forgotten cinematographer and artist Alice Guy emerged in her art. Under Guy’s mask, one could freely admire the naked body of the beautiful, namely male, sex (“Voyeurism of Alice Guy,” 2001) or confess love to the main hero of her childhood, Yuri Gagarin, in a pop-artistic icon (“Alice and Gagarin,” 2010). The space theme increasingly occupied Antoshina in the 2000s, but it was not about the fashion for Russian cosmism, although she also paid tribute to the figures of Tsiolkovsky and Fedorov in several installations and even drew sketches of cosmic and polar cities, playfully parodying Kabakov’s parodic utopias (“Visionary Drawings,” 2009). Her cosmism was of an earthly nature, inspired by the cosmic landscapes of Siberia and overlaid with her fascination with Eastern spiritual practices, meditation, yoga, and pilgrimages to Tibet and Varanasi. Her cosmism, like feminism, implied flights of fantasy, exhilarating infatuation, and graceful wit. Perhaps that is why Tatiana Antoshina’s art has long been appreciated in France – in recent years, she has been living and working in Paris.

In her last exhibition at the Galerie Vallois in Paris titled “Cosmic Ark” (2023), she used ceramic sculpture to depict a not-so-distant future where artists and scientists come together to recreate extinct species of fantastical animals known to us from Bosch and medieval bestiaries. These genetically-engineered artworks would then embark on an intergalactic journey. One of the sculptural compositions represented a battle scene where a space knight aims a blaster at a hungry dragon, from whose mouth the legs of a beautiful princess protrude. It seems that laughter sometimes triumphs not only over evil but also over cosmism and feminism.

Beauty from insignificance: dozens of blue rubber pears are attached to various jars and bottles filled with water – and suddenly poetry, air, extraordinary lightness, Mozartian, improvisational, emerges. The image is both universal and specific: it could be Kitezh, Belovodie, Shambhala, Castalia, or any other fortress of light, or perhaps an ancient Russian city with white-stone churches and onion domes, something from the Golden Ring, from the Vladimir-Suzdal lands. Even the title, referring to a Soviet hit song from the post-thaw era, does not diminish the work, but only adds romance to it. Tatiana Antoshina recalls the sharp sense of melancholy that overwhelmed her during a Sunday trip to Kalyazin, where the quiet melancholy of the flooded temples contrasted with the unrestrained joy of drunken groups who had set out on a river cruise. A day later, in a Moscow pharmacy, she saw blue syringes reflecting in glass shelves like domes in water, and the prototype of the installation formed. “I never intended to offend anyone. I really liked the idea that from some trivial object, you can create something sublime and beautiful,” says the artist. It would seem that in the “Blue Cities” there is nothing but magic and delicate beauty, but they did not save Antoshina from the offended believers: the artwork was included in the exhibition “Rodina” (Motherland), a curatorial project by Marat Gelman, which was shown in Perm, Novosibirsk, and Krasnoyarsk during the protest years of 2011-2012, and became a red flag for the organized public, demanding the exhibition to be banned. However, today all the passions are behind, and the installation “Blue Cities,” a truly museum-quality work, is included in the Museum Fund of the Russian Federation and is stored in a state museum.

- Link to publication in Kommersant Weekend in russian: